- Guides to formal logic for legislative drafters

- Is there any logic in law (or at least in legislation)?

- What logic are we talking about?

- How does formal logic apply to legislative drafting?

- What do we mean by “parsing” the logical structure of a draft of legislation?

Guides to formal logic for legislative drafters

Formal logic is useful for legislative drafters -

- both as a reinforcement for the common sense logic we apply in constructing and checking our drafts,

- and as a bridge to understanding what computers can do with the logical structures in legislative drafts.

But most introductory guides to formal logic are written for students of computer science or mathematics, and head off too soon into specialist complications that are not needed by legislative drafters. Equally, legislative drafters do need a basic explanation of “deontic” logic, which is often treated as too advanced for general introductions to logic.

So our project has tried to explain the basics of formal logic in ways that will make sense to, and be useful for, legislative drafters (particularly those working in the relatively rigorous modern Commonwealth style of drafting).

- Matthew Waddington has published an article on how to apply formal logic to legislative drafting - The basics of symbolic formal logic as a useful tool for legislative counsel (original available through CALC Loophole, November 2021).

- Zoe Rillstone has been running a workshop on logic for legislative drafters at meetings of the Commonwealth Association of Legislative Drafters in the various regions and globally. See her workshop slides, her “logic cheat sheet” and her “truth tables”.

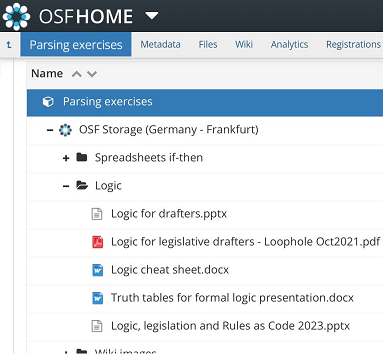

We have gathered these and our other materials in the Logic folder in our “Parsing exercises” documents on OSF.

Is there any logic in law (or at least in legislation)?

Many lawyers are repulsed by the mathematical look of formal logic, and many common lawyers see logic as being a concern of civil law countries. But legislation in common law countries is meant to work logically, and legislative drafters do use common sense logic in checking our drafts.

Against –

- “The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience.” Oliver Wendell Holmes, The Common Law (1881)

- “when lawyers reason or dispute about legal rights and obligations … they make use of standards that do not function as rules” Ronald Dworkin, The Model of Rules (1967)

For –

- Hohfeld, Some Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning (1913)

- Layman Allen, Normalized Legal Drafting and the Query Method (1978)

- Kowalski, The British Nationality Act as a Logic Program (1986)

- Sartor, Fundamental Legal Concepts: A Formal and Teleological Characterisation (2006)

- Governatori, Rotolo & Sartor, Logic and the law: philosophical foundations, deontics, and defeasible reasoning (2021) in Gabbay, Horty & Parent, Handbook of Deontic Logic and Normative Reasoning 2, 655-760

Between –

- Susan Haack, On Logic in the Law: ‘Something, But Not All’

- Sarah B. Lawsky, A logic for statutes - contrasts case-based reasoning, which law schools teach, with rule-based reasoning “as exemplified in much statutory reasoning”, which is overlooked by most law schools but can be analysed logically (she argues for “defeasible” logic instead of standard formal logic)

Legislative drafters –

“If we draft legislation that has logical errors, every other lawyer will want to be the first to point and laugh” - Every legislative drafter ever.

In modern Commonwealth legislative drafting, the legislative drafters are creating relationships between provisions which are expected to be logically coherent -

- One provision of a draft should not contradict another provision of the same draft without the relationship between them being clear (typically by saying one provision is “subject to” the other or applies “despite” the other).

- The drafter has made a mistake if there is a logical inconsistency. A common example is failing to deal with definitions that have some overlap -

- a type of entity is defined and a provision requires those entities to do some act,

- but then another type of entity is defined and prohibited from doing that act,

- but there is some overlap in the definitions of the types of entities,

- so that there are some entities that are both being required to do the act and prohibited from doing it.

What logic are we talking about?

When looking at logic as it relates to legislative drafting and legislation, the first point is that there are logics and that they are languages which have rules and can be parsed -

Types of language – can all be “parsed”

- natural – English, French, Welsh, Jèrriais

- non-natural – logical languages, computer languages

- in between – controlled natural languages – natural language, but following rules so a computer can read it

Types of logic

- common sense logic - which we use to check our drafts

- formal logics - which logicians use to abstract logical structures - different categorisations include propositional logic, predicate logic, deontic logic (about “must”, “must not” and “may”), and defeasible logic (for handling our exceptions, and exceptions to exceptions) - for more on this see the materials in the Logic folder in our “Parsing exercises” on OSF (we will add more here later)

- computer logics - which computers use to operate, and which grew out of formal logic (in turn, a specialised minority of computer languages are “declarative”, like Prolog, making them more useful for handling logical structures like those in legislation)

Key features of formal logic

- Propositions – true/false (binary/“Boolean” opposition) – in our terms, parts of a provision that could be taken out to form complete sentences, which can be turned into questions that we are expecting to be answered “yes” or “no”

- Formal – abstraction with symbols & parentheses – what we are looking at is the form not the content (like algebra)

- Connectors – “not”, “and”, “or” (inclusive/exclusive), “if” (if but not only if, or if and only if) – fixed meanings

How does formal logic apply to legislative drafting?

We are looking at formal logic, particularly propositional logic using “if”, “and”, “or” and “not”. It is just a more sophisticated form of the common sense logic that legislative drafters already use to write their own drafts and to check drafts written by other drafters. We also use deontic logic as a useful way to get legislative drafters to consider more carefully how we use our key tools of “must”, “must not” and “may”, but we favour sticking to if-then logic as the way that drafters should be able to render their provisions.

If-and-or-not - propositional logic

There is often an assumption that, because law deals with the fuzzy world of human shades of grey, binary true/false models will not work. But legislation does work in a binary way, even when though it is inevitably vague (keeping in mind the distinction between vagueness and ambiguity) - either the legislative provision applies or it doesn’t.

- If we provide that using “reasonable force” is not assault, then a court has to decide to decide not guilty or guilty, by answering “yes” or “no” to whether the force used was “reasonable”.

- There is no in-between, even though the individual scenario will be unique and complex with many shades of grey - a jury asked for “guilty” or “not guilty” cannot say “well, life isn’t really that black and white, you know”.

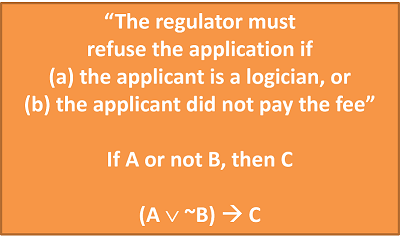

The key is that most legislative provisions apply a legal effect if certain conditions are met (but those conditions might be cumulative or alternative, and some of them might be expressed negatively).

- This has a logical if-then structure, with and-or-not structures in the conditions.

- The conditions can be turned into questions which must be answered “yes” or “no”.

- The human reader of the legislation often finds these structures confusing, particularly when we have to provide exceptions to exceptions and generally cater for the complexity of human activity.

- But the human reader can be guided through the logical structures by a computer, given that computers can follow logic easily and reliably.

“Must”, “must not”, “may” - deontic logic

Deontic logic works on obligations, prohibitions and permissions, for which legislative drafters in the Commonwealth now mainly use “must”, “must not” and “may”. A typical version works with “O” for “it is obligatory that” (or “must”), and then uses negation (“~”) to create prohibition and permission - so OX means “must do X”, “O~X” means “must not do X”, and “~OX & ~O~X” means “may do X” (needn’t do X and needn’t not-do X).

- It is very useful for helping us ensure we are clear about what happens if the conditions for imposing an obligation are not met - the negation of “must” is “need not”, rather than “must not”.

- It is also a prompt to think more carefully about what we use “may” for (and how “may not” can legitimately be used) -

- sometimes for a permission, to mean you are neither obliged nor prohibited (as in “~OX & ~O~X”)

- but sometimes to introduce a power, so that if you do something (that you weren’t prohibited from doing anyway), it will now impose some obligation or prohibition on someone else (as in “if xyz, an officer may serve a notice … the person served must comply with the notice”)

- and too often just to express factual possibility, where “might” would normally be better (particularly in the increasingly deprecated “as the case may be”).

For more on this see The basics of symbolic formal logic as a useful tool for legislative counsel.

Much of the technical work on computational law has gone into deontic logic, to produce sophisticated reasoning. But we believe legislative drafting offices should only produce a basic if-and-or-not version of their drafts (which the more sophisticated systems can draw on), without trying to use deontic logic.

- Because of the difficulties in identifying genuinely normative provisions that happen not to use “must” (particularly treating offences as prohibitions) and non-normative provisions that do use “must”, it makes sense to us to analyse “must” provisions as just if-then.

- We do that by adding an implied provision “if the person/thing does not do what they must do, then they count as in breach of this provision”.

- We can then use that as a link to the consequence of a breach - “if the person/thing counts as in breach of this provision, then they commit an offence” OR the notice is not valid OR whatever other consequence. There must always be some consequence (although it might be implied, as when we impose a public law duty on a public body) or the drafter would not have used “must”.

- This also avoid problems that traditional deontic logic has with degrees of prohibition (the “gentle murderer” paradox). We are happy with the idea that robbery is theft with violence and carries a higher penalty (which if-then logic can cope with), but deontic logic struggles with the idea that all theft is prohibited and then theft-with-violence is somehow more prohibited.

- By the way, we are not saying that every “must” should replaced by a neutral offer to the citizen of a legitimate choice of complying or taking the consequences. In “if X, then Y must do Z” we treat “Y must do Z” as a genuine legal result of X. We do that as well as moving on to add “if Y must do Z but does not do Z, then Y counts as in breach of this provision”, rather than skipping the “must” and moving straight on to the consequence of breach.

- Also we are not alone in doing without deontic logic. Both AustLII’s DataLex and Robert Kowalski’s Logical English prefer not to use it.

In fact most of the technical work on computational law is on defeasible deontic logic.

- Defeasibility is the idea that a legal rule is not determinative because there are always other contradictory competing legal rules which trump it or are trumped by it, so that a non-traditional logic is needed.

- That is useful if you want to capture the entire legal system and make final decisions about a person’s overall legal position. But we are only trying to capture what the legislation says on its face.

- In Commonwealth drafting we follow the principle that there should not be unresolved contradictory rules inside one piece of legislation, in that their relationship should be expressly spelled out (at least with “This section applies subject to / despite section X”).

- Then if the approach is just to ask “what does this provision say on its face”, that means that the exceptions can be expressed with ordinary if-then logic catering for all the exceptions that are on the face of that piece of legislation.

(We will post more about deontic and defeasible logic later.)

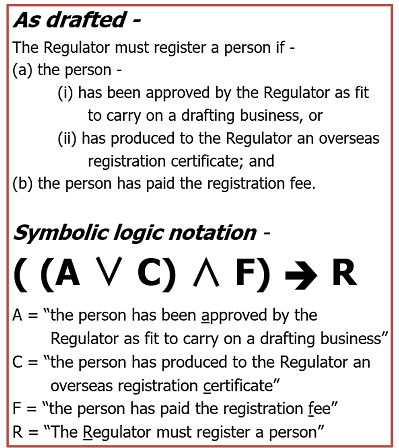

What do we mean by “parsing” the logical structure of a draft of legislation?

Parsing in grammar is something legislative drafters will already be familiar with. It is identifying the part of speech for each word in a sentence (the grammatical function of the word), and the relationships between them, as in “that is an adjective and it qualifies this noun”.

Parsing in logic is similar - our sentences can be treated as propositions and you can find the logical structure of the sentence by identifying the words that have logical functions and the ones that are being related to each other with those logical functions. In

“a person who drives must wear a seatbelt”

the logical structure is an if-then proposition -

- the logical word is “who” which represents “if”,

- the condition is “a person drives” and

- the effect is “a person must wear a seatbelt”

IF a person drives THEN a person must wear a seatbelt.

The logic is more complex when we add lists joined by “and” or “or” and when we start negating some of the elements of the sentence.

- In “A person must wear a seatbelt if the person drives and is not a police officer who is on duty or is responding to an emergency”, there is ambiguity about whether the person responding to an emergency needs to be a police officer or whether that could be any person.

- Legislative drafters might fix that by breaking the sentence into paragraphs with different indentation and numbering - “A person must wear a seatbelt if the person - (a) drives and (b) is not a police officer who - (i) is on duty or (ii) is responding to an emergency”

- There are different forms of logical notation, but one way to render the logic of this would be “IF ((the person drives) AND ( NOT ((the person is a police officer who is on duty) OR (the person is a police officer who is responding to an emergency))) THEN (the person must wear a seatbelt)”

The purpose in each case is to capture the point that the person responding to the emergency needs to be a police officer if they are going to drive without a seatbelt.

For more on how we parse the logical structure in legislative provisions, see -

- Parsing drafts for if-then logic – video from CALC conference 2022;

- Jersey’s project on parsing drafts for if-then structures for “Rules as Code”, Waddington, CALC Loophole, Sept 2023

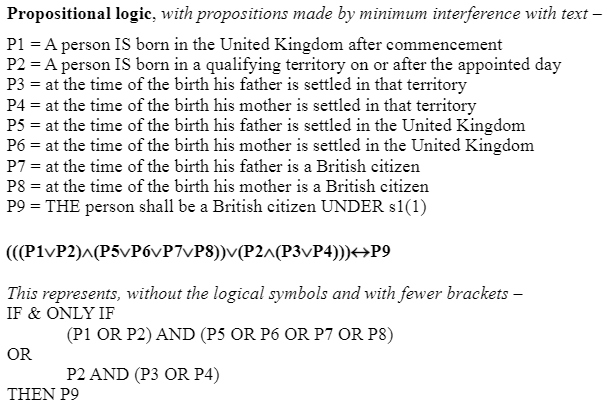

- our paper on ways to parse s1 British Nationality Act 1981 (the provision that kicked off computational law with the foundational paper by Kowalski and others applying Prolog to it back in 1986)

This page is a work in progress. We plan to add explanations of propositional logic, and more on why we are using if-then rather than going into deontic logic or defeasible logic. You can find the documents we produce on OSF: https://osf.io/bkjqx/.